Alabama kids make record summer learning gains after starting with record low assessment scores

Montgomery Advertiser

As the 2020 school year came to a close, one boy in Greensboro, Alabama, finished the first grade without being able to spell his name.

He didn’t meet the reading benchmark for his age group, either, and so the Greensboro Elementary School counselor invited him to attend Sawyerville Summer Learning camp for reading intervention.

On the final day of the three-week program, summer learning coordinator Breanna Mitchell said the boy marched straight into a group of camp interns and proudly sang a song they had taught him to spell out his name.

“When he gets done, everyone just yells because they are so excited for him. He just had the biggest smile on his face,” Mitchell said. “We face issues like not being able to know sounds, or words or letters, but I think we met every student where they were.”

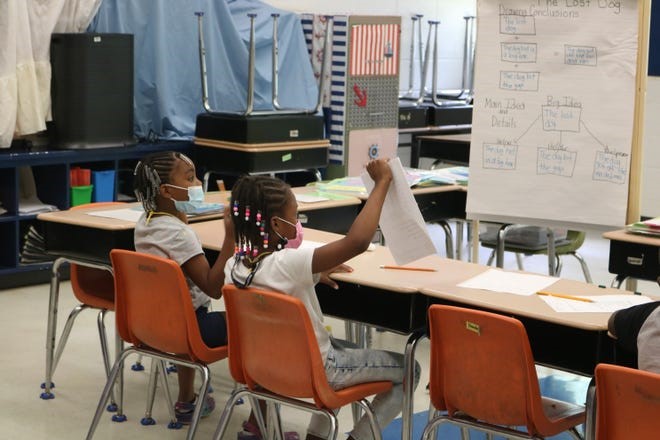

Sawyerville is one of 35 summer learning programs in Alabama that are part of Summer Adventures in Learning (SAIL), a network that provides funding, testing and collaboration opportunities for groups dedicated to preventing the “summer slide.”

On average, students’ test scores decline by about a month of learning over summer break, and lower-income students tend to experience greater reading losses, according to the Brookings Institute.

‘COVID loss’ contributes to low scores

This year, though, summer learning program directors said they were also battling “COVID loss,” the gap in progress made in at-home learning versus what would have occurred with in-person school.

At the start of this summer, assessment scores among approximately 2,000 Alabama kids participating in SAIL programs showed the lowest reading and math proficiency rates since SAIL began almost a decade ago.

However, the programs recorded new highs in academic growth by the end of the summer.

On average, SAIL students tested in the 21st percentile of reading and the 23rd percentile of math for their age groups before completing the summer learning camps. After completion of the summer learning programs, though, they averaged gains of 3.2 months in math and 2.6 months in reading.

On average, SAIL students tested in the 21st percentile of reading and the 23rd percentile of math for their age groups before completing the summer learning camps. After completion of the summer learning programs, though, they averaged gains of 3.2 months in math and 2.6 months in reading.

The network uses the Renaissance Learning Systems Star Assessments for its testing.

“SAIL kind of came together around this mission of thinking that every child needed a chance for a successful life, and we discovered a really successful, impactful way of doing this through summer learning,” said Jim Wooten, chairman of the SAIL board. “You have to nurture the whole child: mind, body and spirit.”

Based in Birmingham, the network provides grants and additional support to programs in North Alabama and the Black Belt region as well.

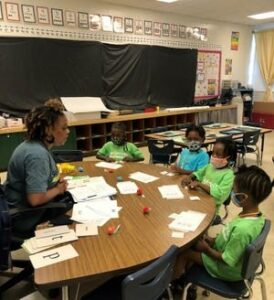

BAMA kids, a summer and after-school learning program that operates in Wilcox County, is one of five programs in the Black Belt that SAIL funded this summer.

“The majority of our participants are from low resource households because of the area where we live,” BAMA Kids director Sheryl Threadgill Matthews said. “The unemployment rate is relatively high, and in the Black Belt, we face a lot of struggles anyway because our tax base is low, and we don’t have the same advantages as people do in the metropolitan areas.”

“The majority of our participants are from low resource households because of the area where we live,” BAMA Kids director Sheryl Threadgill Matthews said. “The unemployment rate is relatively high, and in the Black Belt, we face a lot of struggles anyway because our tax base is low, and we don’t have the same advantages as people do in the metropolitan areas.”

Matthews worked with her community to start the program almost 30 years ago because local kids didn’t have access to other after-school or summer programs like the YMCA or Boys and Girls Club.

BAMA Kids has now operated with SAIL support for the past four summers.

The organization works to provide children in Wilcox County with whatever resources they need for academic success, from school supplies, to book clubs, to transportation.

“Even if the test scores don’t go up as much as we would like or as they would like, we know that our youth were impacted,” Matthews said. “We know that they received life skills every day. We know that they received intense reading intervention.”

Apart from the typical learning and resource challenges that these summer learning programs confront on an annual basis, the pandemic created its own difficulties.

“This summer, we had lots of anecdotal reports from our programs that the kids came in much less socialized. They had clearly shown negative impacts from not being in school and in their normal activities,” Wooten said. “We wound up having to put together a lot of team building and relationship building activities. We always do that to some degree, but this year, we had to do it to a much greater degree.”

Staff members at Sawyerville Summer Learning and BAMA Kids both echoed the issue of socialization.

Staff members at Sawyerville Summer Learning and BAMA Kids both echoed the issue of socialization.

Crystal Jones, the Sawywerville director for programming and operations, said it took some of the children all three weeks of the program to open up.

“So many of the kids, especially the younger kids, have been with their parents or their family for so long,” Jones said. “Not only this summer were we teaching them how to read and how to do math, and how to have a love for school and a love for learning, but we were also helping them learn how to interact with other kids and be kids again.”

With this year’s summer programs behind them, SAIL is looking to summer 2022. Grant applications are due in early October, and SAIL plans to finalize its programs by mid-December.

Hadley Hitson covers the rural South for the Montgomery Advertiser and Report for America. She can be reached at hhitson@gannett.com.